Scenarios for IBAN/name check for instant payments and beyond

The legislative proposal on Instant Payments (SCT Inst) by the European Commission (EC) is set to have considerable impact on Payment Services Providers (PSPs), as outlined in our previous blog. One effect of this legislative proposal will be to make the IBAN/Name check mandatory in order to reduce fraud in instant payments. Under the proposal, PSPs will be obliged to implement the service 12 months after the regulation has entered into force (exact date is unknown at the moment of writing). However, the current landscape is fragmented, scattered with several solutions that are not interoperable. In this blog, we outline three likely scenarios for the development of the IBAN/Name check across the SEPA area.

The IBAN/Name check, also known as Confirmation of Payee (CoP), is a relatively new functionality in the PSP’s toolbox. It enables communication between the originator PSP and the beneficiary PSP to validate whether the beneficiary’s name and IBAN as filled in by the originator are a full match, a close match or no match. This helps to reduce cases of payment errors and authorised push payment (APP) fraud resulting from misdirected payments, as well as to increase trust for both payer and payee. At the same time, it reduces client support requests from customers eager to retrieve misdirected payments, thereby reducing the effort PSPs need to spend on investigations and callbacks.

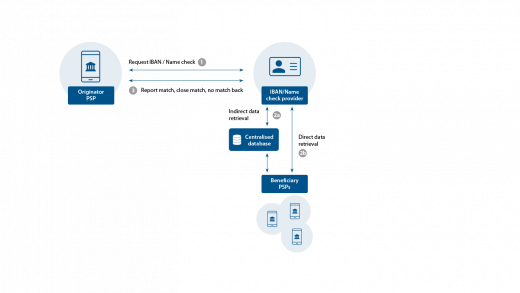

Figure 1 illustrates a high-level flow of an IBAN/Name check between originator PSP, beneficiary PSP and IBAN/Name check provider.

As illustrated in the second step in Figure 1, there are two options for accessing PSP data to conduct the IBAN/Name check:

- Centralised data storage (step 2a): IBAN/Name check provider gathers data (e.g. via files provided by PSPs) in a central database (e.g. in the Netherlands)

- Decentralised data storage (step 2b): IBAN/Name check provider accesses PSP data directly at the source via APIs (e.g. in the UK by connecting APIs to existing open banking authorisation servers).

There are two different types of commercial providers in the IBAN/Name check space. One group of providers, such as EBA Clearing, offer CSM-based solutions whereby IBAN/Name check functionality is part of a broader value proposition, e.g. a Fraud Pattern and Anomaly Detection (FPAD) solution. The other group is made up of specialised providers (e.g. Bluem, Surepay, LUXHUB). that are developing commercial web/app-integrated IBAN/Name check solutions for banks and other corporates who can leverage such functionality in their workflows (e.g. for onboarding, payouts).

In addition, the first scheme-based initiatives are starting to emerge. These aim to consolidate different IBAN/Name check solutions currently available on the market (e.g. in the UK, Nordics) by framing a set of rules to which the solutions need to adhere in order to make them interoperable with each other. These initiatives are elaborated on further below.

INTEROPERABILITY IS ESSENTIAL FOR THE SUCCESS OF IBAN/NAME CHECK

Currently, the landscape is scattered with several solutions that are not interoperable. Such solutions (e.g. Bluem, Surepay, NEXI, EBA Clearing) are based on self-established algorithms, standards and features relevant for their respective geographical focus. The above-mentioned differences in data storage also contribute to this fragmentation.

In light of mitigating this fragmentation issue, the following two regional scheme initiatives have been launched so far:

- Pay.UK has developed an IBAN/Name check scheme, which was mandated to be implemented across all UK PSPs and financial institutions by June 2021. PSPs are free to choose their vendors as long as they adhere to the scheme.

- The Nordics Payment Council (NPC) released a scheme in October 2020. Focus of the scheme is more on the standardisation of messages, rather than the rules for identification of mismatches. On top of that, this scheme is not mandatory, although most Nordic PSPs and financial institutions already offer the service to their customers.

In line with the different approaches and types of solutions that exist, we currently foresee three possible scenarios for the development of the IBAN/Name check across the SEPA area in the context of the EC’s recent legislative proposal for mandating SCT Inst.

SCENARIO 1: MANY LOCAL SOLUTIONS WILL EMERGE AND NEED TO CONNECT TO ONE ANOTHER

In this scenario, the EC leaves the IBAN/Name check open to the market, just as it is right now. This means that all vendors, or individual PSPs, create their own solutions based on their target audience’s wants and needs. This can be detrimental to the interoperability of solutions. In such a scenario, vendors will only focus on interoperability within their own country, since there is little reason to create reach due to the majority of payments being domestic. Additionally, this focus on a local solution and consideration of country-specific differences – such as identifying and accounting for minor variations in the name (e.g. abbreviations, nicknames or alternative spellings) – will lead to the creation of very fragmented algorithms. This is another factor that is not favourable for solution interoperability.

While this scenario would result in a landscape with numerous service providers competing for customer success, it would hamper efficient use of the IBAN/Name check at scale. Moreover, to create reach in this scenario, multiple local solutions must connect to each other, requiring supplementary effort.

SCENARIO 2: DEVELOPMENT OF A SEPA-WIDE IBAN/NAME CHECK SCHEME

In this scenario, the EC pushes for a pan-European scheme rulebook for the IBAN/Name check, potentially developed by the European Payment Council (EPC), similar to Pay.UK or the Nordics Payment Council (NPC) initiative. If the EC would make this scheme mandatory, all existing and future IBAN/Name check vendors would need to adhere to specific guidelines, standards and rules to ensure interoperability across the SEPA area. This would ease decision-making for PSPs, as they could choose from multiple solutions that all are interoperable with one another based on the same standards. The advantage of such a scheme would be the resulting interoperability of solutions and the mitigation of APP fraud at scale, as the verification of IBAN numbers with names could happen across services providers and geographies. The disadvantage would be that existing players might need to modify current solutions to adhere to the scheme.

Alternatively, a harmonisation initiative (similar to Berlin Group with PSD2) will be introduced, setting inter-PSP and solution-provider technical standards, for example, or data access standards to favour standardisation. The advantage of such an initiative is that standards would be available for providers to build solutions upon. However, such harmonisation initiatives are usually not mandatory, so this would still leave plenty of room for fragmentation.

For this scenario to happen, key payments industry actors need to act fast and collaborate, because various solutions are already rapidly emerging to tap into the opportunity. This might mean if a scheme is introduced by the EPC in the upcoming months, they might be late to the game.

SCENARIO 3: THE WINNER TAKES IT ALL

In this scenario, a single player with a first-mover advantage becomes the dominant pan-European player. This is possible because the player has a head start in terms of geographical reach and accounting for geographical differences, and will therefore be a favoured solution provider for PSPs implementing such functionality.

The advantage of such a scenario is guaranteed interoperability, as everyone has the same provider and thus the same solution. This would make it possible to have a central database with continuous data inflow from all PSPs, for instance, so that the solution can be continually improved going forward. The disadvantage of such a scenario is that it introduces monopolistic behaviour and does not leave much room for competition in the market. Additionally, it would mean having one single point of failure, resulting in additional risk and data security concerns as well as additional requirements to have fallback mechanisms in place. On top of that, regulators in general are not expected to accept sensitive data being stored abroad.

For this scenario to happen, a dominant solution must emerge in the short term that is also able to stay ahead of all other solutions currently appearing on the market thanks to being the preferred partner for PSPs. This requires dynamic scalability of the solution (whereby computing resources are automatically adjusted as the number of required IBAN/Name checks increases), understanding of different market dynamics and requirements, and operational capacity.

THE FUTURE FOR IBAN/NAME CHECK IS STILL UNCLEAR

Although the IBAN/Name check clearly has potential benefits, it should be noted that an IBAN/Name check alone is not sufficient to mitigate the many types of fraud a PSP can encounter (e.g. money mules, card fraud, account takeover, etc.). Therefore, the IBAN/Name check must be part of a PSP’s broader fraud prevention strategy. On top of that, having corporates access the service in the future as well, will contribute to the success of IBAN/Name check.

If fragmentation persists due to new solutions continuing to enter the market, the ideal outcome would be that the EC will push for the payments industry to organise itself and publish standards around the IBAN/Name check functionality. This would foster harmonisation, extend the reach SEPA-wide and create a level playing field for solution providers, making the investment in the IBAN/Name check worthwhile for PSPs.

Stay tuned!

Contact us