Web 3.0: How decentralisation and incentives will create alignment on the internet

There have so far been two major ‘phases’ of the internet, which are now retrospectively referred to as Web 1.0 and Web 2.0. Opinions differ on the precise beginning and end of these two phases, so the periods are not clearly defined – and the burgeoning Web 3.0 phase is no different.

The first two phases of the internet

Although there are many ways to look at the evolution of the internet, the two perspectives that seem most relevant in light of Web 3.0 are functionality and decentralisation.

During the first phase, internet services were built on open protocols that were controlled and governed by internet communities, meaning that the internet was chaotic and highly decentralised. Equitable access led to an explosion of creative innovation and competition. There was one important challenge, however: commercialisation. A lack of financial incentives slowed down the development of open protocols.

The user-generated content resulting from the ability for everyone to both read and write was effectively commercialised in the second phase of the internet. This commercialisation allowed tech companies to build software and services more quickly, eventually outpacing open protocols. This gave rise to a plethora of centralised (social) services. Accelerated by the explosive growth of smartphones, mobile social applications came to account for the majority of internet use. This ‘Social Web’ onboarded the world onto the internet as it gave people access to amazing technologies, many of which were free to use.

In short, the absence of commercialisation of open protocols in Web 1.0 led to commercialisation on centralised platforms. However, this came at a cost – most importantly in terms of diminished competition and misalignment between the platforms and their users.

The predictable flaws of centralised platforms in Web 2.0

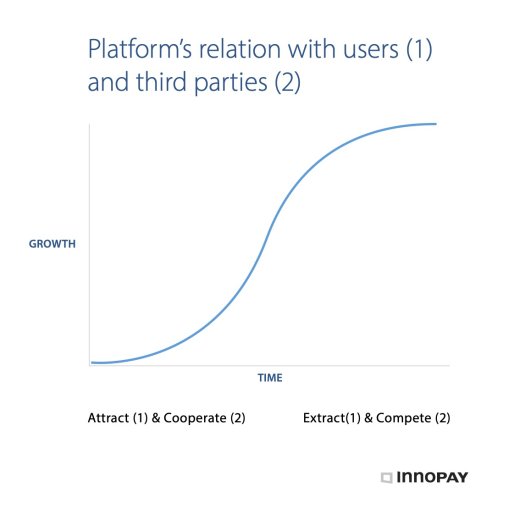

Centralised platforms follow a predictable life cycle. It typically starts out in a positive-sum situation for the platform, its users and third parties, but it ends up as a zero-sum situation with misalignment between them.

Since platforms are systems of multi-sided network effects, the main challenge is to bootstrap the network. This typically requires the subsidisation of a particular side of the market. In the case of social platforms, this tends to be the users and third parties developing/building businesses on top of the platform. The money to fund these subsidies is raised in large venture capital rounds. Initially, these platforms enjoy positive feedback loops that create a network effect. As the platform grows, however, frictional effects can slow down the growth rate. This creates the typical S-curve of adoption.

This is the point where the company’s shareholders come in. Ultimately, the company has a fiduciary obligation towards its shareholders. It is expected to put the welfare and best interests of the corporation above their own personal or other business interests. Platforms will inevitably choose to extract more value from users’ data and start competing with third parties that build services on top of their platforms to increase market share and profits.

As a result, in Web 2.0 both users and third parties began to distrust centralised platforms. It became increasingly hard for startups, innovators and creators to build and grow their business on top of centralised platforms without having to worry about the platforms starting to compete with them or abusing their power to stifle innovation. Users felt robbed of their data and the value they provided to the platform, and started demanding compensation. The root of this misalignment is a separation of financial benefit and utility. The financial benefit is attributed to venture capitalists and shareholders, while users only benefit from the utility of the platform. This only became apparent as the platforms and their markets matured beyond their initial success.

Enter Web 3.0, a stateful (re)decentralised internet that aligns all participants

The term Web 3.0 went mainstream in 2021, although it had actually been floating around in the crypto community since Ethereum co-founder Gavin Wood coined the term in 2014. The Web 3.0 community aims to (re)decentralise the internet to counter the increasing power of centralised platforms – much like in Web 1.0, only this time with stateful protocols instead of stateless protocols. State-what? The protocols underpinning today’s internet are incapable of maintaining what computer science refers to as ‘a state’. In simple terms, they cannot maintain the status of who is who, who owns what, and who has the right to do what. And if you can’t maintain a state, you can’t transfer value using the internet as a transaction medium and will therefore have to resort to centralised platforms and institutions to act as transaction intermediaries. The fact that internet protocols were stateless was the core reason that centralised platforms were an inevitability in Web 2.0.

However, Web 3.0 is built on the premise of stateful protocols based on blockchain technology and other distributed ledger technologies. It means that the internet gets a built-in settlement layer, or rather multiple layers to be more precise. This enables P2P transactions to take place almost instantly without requiring any centralised intermediaries.

Incentives and alignment

Web 3.0 can realign all stakeholders on the internet and restore the imbalance that centralised platforms have created. Decentralisation is a big part of that, because it prevents the extraction of value from platform users and boosts competition and creativity as discussed above. But Web 1.0 protocols were decentralised too, so what’s different this time around? Well, the secret sauce that Web 1.0 lacked was incentives.

Web 3.0 protocols have a native token that is used to incentivise and align all stakeholders to contribute to the shared goal, which is network growth and appreciation of the token’s value. These incentives draw in developers, entrepreneurs, investors and users. This alignment of all network participants results in network effects that are even stronger that those of Web 2.0 social platforms. It’s the main reason that causes people – even sophisticated technologists – to consistently underestimate the potential of decentralised platforms.

So, incentives are what make these stateful protocols different from their stateless Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 counterparts. A ‘tokenised network’ with correctly engineered ‘tokenomics’ (which is a fancy word for incentive structure) solves a lot of the bootstrapping issues that existed in both previous phases of the internet. In Web 1.0, internet protocols were community-governed and decentralised, but there was no commercial model behind them, leaving them completely dependent on the contribution of volunteers.

In Web 2.0 platforms have to fund the entire bootstrapping process through venture capital funding, which isn’t easy! First, they have to hire a lot of developers to build the product, and bearing in mind that developers are expensive, a lot of funding has to be raised. Then they have to bootstrap a multi-sided network and attract users. This requires subsidising some sides of the network (typically by offering the product for free) to bootstrap it, which once again calls for substantial funding. If they make it through those challenges, they usually still don’t make a profit for a long time (if ever), largely due to the heavy subsidising. These dynamics introduce high barriers that make it very hard for Web 2.0 platforms to be successful, but when they do overcome these barriers and garner enough network effects, they typically become very successful, up to point where they become monopolies.

Because of the built-in incentives, tokenised networks provide a better alternative to bootstrapping. They have a significantly more attractive value proposition for both developers and entrepreneurs. If they see value in the protocol, their participation in growing the network is rewarded. The same goes for users. Through token airdrops or token sales, early users can be incentivised to start engaging with the protocol at a really early stage, providing valuable input to the developers of the protocol. Users who want to see the project succeed are incentivised to become ambassadors. This is in stark contrast to the way things were done in Web 2.0.

Thanks to these built-in incentives, even if Web 3.0 protocols start out half-baked without any use cases, the developer community and entrepreneurs can be relied on to finish the products and build use cases on top of the protocols.

As a result, the decentralisation and tokenisation of Web 3.0 protocols has drawn in – and will continue to draw in – incredible creativity. The pace of innovation is staggering and continues to increase, to the point where it is now almost impossible to keep up with the latest developments.

No one knows where Web 3.0 will eventually end up, but in view of the massive amount of talent and creativity that is coming to the space it will undoubtedly continue to surprise us. It’s an exciting journey that we are all going on together. Join us for the ride!