The Pulse of Open Banking in the U.S. - leading on APIs, but lagging on developer experience...and unclear on regulation

Given recent developments around the introduction of Section 1033 in the US, this blog takes a closer look at the current state of Open Banking in the country.

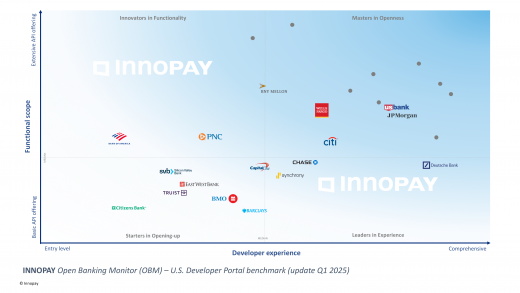

To do so, we will apply INNOPAY’s Open Banking Monitor (OBM). Since 2017, the OBM has provided global insights into the industry by analyzing various developer experience features - categorized into 3 dimensions: API Documentation; Developer Usability; and Community & Ecosystem Development - as well as API functionalities, referred to as Functional Scope (see Figure 1 below). For more details on the Section 1033 regulation itself, please seek out our previous blog “Section 1033: From Market Led to a regulatory approach via Section 1033”.

U.S. Open Banking functionalities are currently largely dominated by Payment and Account Information use cases, with treasury management in particular being the most offered. In contrast, developer experience across the observed banks still has room to improve, as the focus appears to be on providing only basic features. A visual representation of the status quo can be seen in Figure 2 below. Given the large number of banks active in the states, the overview highlights that a significant number of financial institutions with U.S. operations have yet to embark on their Open Banking journey (and have therefore not been assessed as part of this analysis).

1. U.S. API Functionalities: Treasury management as killer use case

APIs to allow corporate customers to seamlessly integrate treasury management functionalities currently represents the most widely adopted use case among leading U.S. banks. Treasury management APIs largely consist of various payment initiation and account information functionalities that enable banks’ corporate customers to:

Originate payments using different rails (e.g. ACH, RTP, FedNow, Wire, checks, and international options such as SEPA);

- track the status of payments;

- easily onboard new virtual accounts and validate customer accounts;

- access a broad scope of account data in real-time (e.g. account balances, transaction history, and statements).

These APIs enable banks to improve clients’ user experience with treasury management solutions by embedding key functionalities in their software platform of choice and streamlining real-time access to data at the point of need. Payments, account information, and account management functionalities currently account for the majority of APIs at 68% (see Figure 3 below).

In addition to treasury management, several banks also offer APIs for the issuing and/or management of (credit) cards. The observed APIs within the card space target both retail and business customers. Typical use cases consist of allowing customers to browse and/or apply for pre-screened or personalized credit cards and managing virtual cards and corporate card accounts. In addition to the large U.S. financial institutions such as US Bank, Capital One, or Chase, some foreign banks such as Barclays are also trying to capture a share of the lucrative U.S. (credit) card market. U.S. consumers continue to favor cards, with debit-, credit- and prepaid cards accounting for 49% of eCommerce and 71% of point-of-sale spending volume in 20241. This does not even account for card-based digital wallets such as Apple Pay. Such APIs allow banks to extend the reach of their card products while customers benefit from a modernized user experience that is both faster and easier to use.

Besides the product categories mentioned above, a handful of banks also offer additional APIs that complement existing product lines. Such examples include investment & foreign exchange APIs to execute trades and manage trading activity (e.g. Wells Fargo, Bank of America & Deutsche Bank); or digital identity APIs to leverage existing customer data for onboarding processes and data verification (e.g. Capital One, Synchrony). Furthermore, some banks also offer merchant checkout solutions to enable the acceptance and processing of online payments (e.g. J.P. Morgan). One functional API category that remains rather underrepresented in the U.S. is lending APIs. Despite the large opportunity presented by lending, with SME and consumer purchase financing standing out as key use cases, only a select few banks offer APIs for loan product origination and adjacent functionality (e.g. Capital One’s Auto Finance). As can be seen in Figure 3 below, lending APIs only account for ~2% of APIs offered by the banks included in our sample. This could therefore present an additional opportunity for U.S. banks to explore.

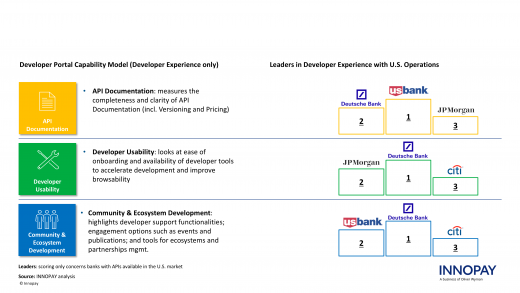

2. U.S. Developer Experience: Solid API Documentation, rest still needs to catch up

Developer Experience is an area that so far has not necessarily been prioritized by U.S. banks. The developer experience is a critical element of successful software development and significantly impacts how users perceive the quality of a product. While most observed banks already have solid API Documentation in place to provide developers with the essential information to understand the API and its functionalities, features beyond such essentials are often still lacking. In fact, Developer Usability features, such as tools to guide developers on how to get started and go live; manage and test applications; and accelerate the development process (e.g. SDKs) still appear to be rather scarce. These tools are very impactful as they remove potential friction and improve the customer experience. Community & Ecosystem Development features appear to be even less of a priority for most players as it takes time to build up a partnership network and a more mature API portfolio.

Only support features such as ticketing are considered a must have in this category but these are already being offered by most banks.

Nevertheless, a handful of players are offering a leading experience. J.P. Morgan’s Payments portal stands out due to its excellent Developer Usability. Furthermore, US Bank and Citigroup shine due to their investment into Community & Ecosystem Development features such as a marketplace for partner integrations. As investments into publications and content to form and engage developer communities have not borne as much fruit as foreseen (less players offer publications or organize events compared to previous OBM assessments), the focus of U.S. Banks trying to improve in this category should be on features concerning developer support. This means implementing features to minimize friction and to facilitate the development of an ecosystem as well as partnership network. A visual representation of leaders in Developer Experience with U.S. operations can be seen in Figure 4 below.

3. Market developments: Increasingly less ‘Open’ Banking & regulatory uncertainty

Another trend of note concerns the ‘openness’ and scope of developer portals in the country. Developer portals in the U.S. are becoming increasingly less ‘open’, as more content and functionalities such as API specifications and sandbox environments are only accessible for (pre-)approved users. Unfortunately, developer portals of some U.S. banks remain inaccessible altogether and could therefore not be (fully) included in this analysis.

Additionally, a few banks are moving to create specialized developer portals for specific use cases and/or customer segments. Citigroup, for example, now offers ‘Consumer’ and ‘Institutional’ APIs on separate developer portals (linked to on developer portal landing page). Such a more targeted approach aims to make it easier for developers to find the products and information they need without having to browse through content intended for a different audience. When utilizing this approach, it is critical that these different portals all achieve a high degree of discoverability through search engine optimization and information does not become too scattered over multiple pages. It also often entails higher maintenance efforts and costs.

In another potentially even more significant shift for the industry, J.P. Morgan recently announced plans to charge Open Banking data aggregators, such as Plaid, for access to its customer data later this year. As the largest bank in the country, this decision could have a transformative impact on U.S. Open Banking and pose a substantial challenge to the business models of such FinTech companies. These firms rely on free API access to customers’ financial data to process transactions, run analytics and KYC/fraud mitigation.

J.P. Morgan, however, has emphasized that it has made considerable investments in infrastructure to secure customer data, even without the prospect of a direct return on investment. The bank also noted that the high volume of API calls places significant strain on its IT infrastructure. In contrast, Open Banking advocates have criticized the bank’s intentions given that customers owning their own data and not the financial institution is one of the core principles of Open Banking.

This development comes amid ongoing turbulence surrounding the Open Banking rule of Section 1033, with the CFPB actively seeking to repeal the rule it once proposed. Instead, the Bureau has now decided to significantly revise the rule and provide improved justification as part of what it calls “an accelerated rulemaking process”. The original regulation would have mandated banks to provide free access to customers’ data from various account types, including checking and savings accounts, credit and prepaid cards, and digital wallets. Now, instead of fostering competition as originally intended by Section 1033, the banks’ ability to monetize customer data could undermine FinTech competition by limiting their access to essential resources. However, a new rule proposal could once again shift the trajectory of Open Banking in the U.S.

Conclusion

While some new banks have been added and leading banks have made progress since the last OBM update, the breath of the market remains limited to a handful of financial institutions given the vast number of banks active in the country. The implementation of Section 1033 could have the potential to significantly alter the state of Open banking in the United States. For several banks, section 1033 would mean dedicating resources to Open Banking for the first time. Even for the 17 analyzed banks above, there would still be functional gaps concerning the latest proposed scope that would need to be closed. The regulation would also have the potential to further jumpstart adoption as many might explore further use cases once the opportunities presented by Open Banking have become more apparent. Such regulation has proven to be a significant catalyst to drive innovation in markets such as the U.K., which now has over 11.7 million active Open Banking users2. It is important to note that this includes payment use cases as U.K. users now initiate over 22.1 million open banking payments monthly2, which would not be part of the initial 1033 scope. However, given the recent developments around customer data monetization, U.S. Open Banking may be headed down a completely different path after all.

This article by INNOPAY is the second of two articles that cover the Open Banking market in the US, with the first articles covering the basics about Section 1033 and what it entails. Make sure to subscribe to our newsletter to not miss any new publications!

[1] 10th Edition of the Worldpay Global Payment Report (GPR 2025)

[2] PSR and FCA set out next steps for open banking, as published by the Payment System Regulator on 23 January 2025